Wyeth in Taiwan

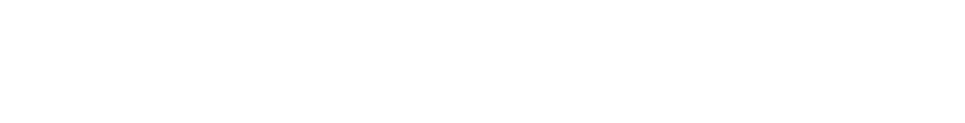

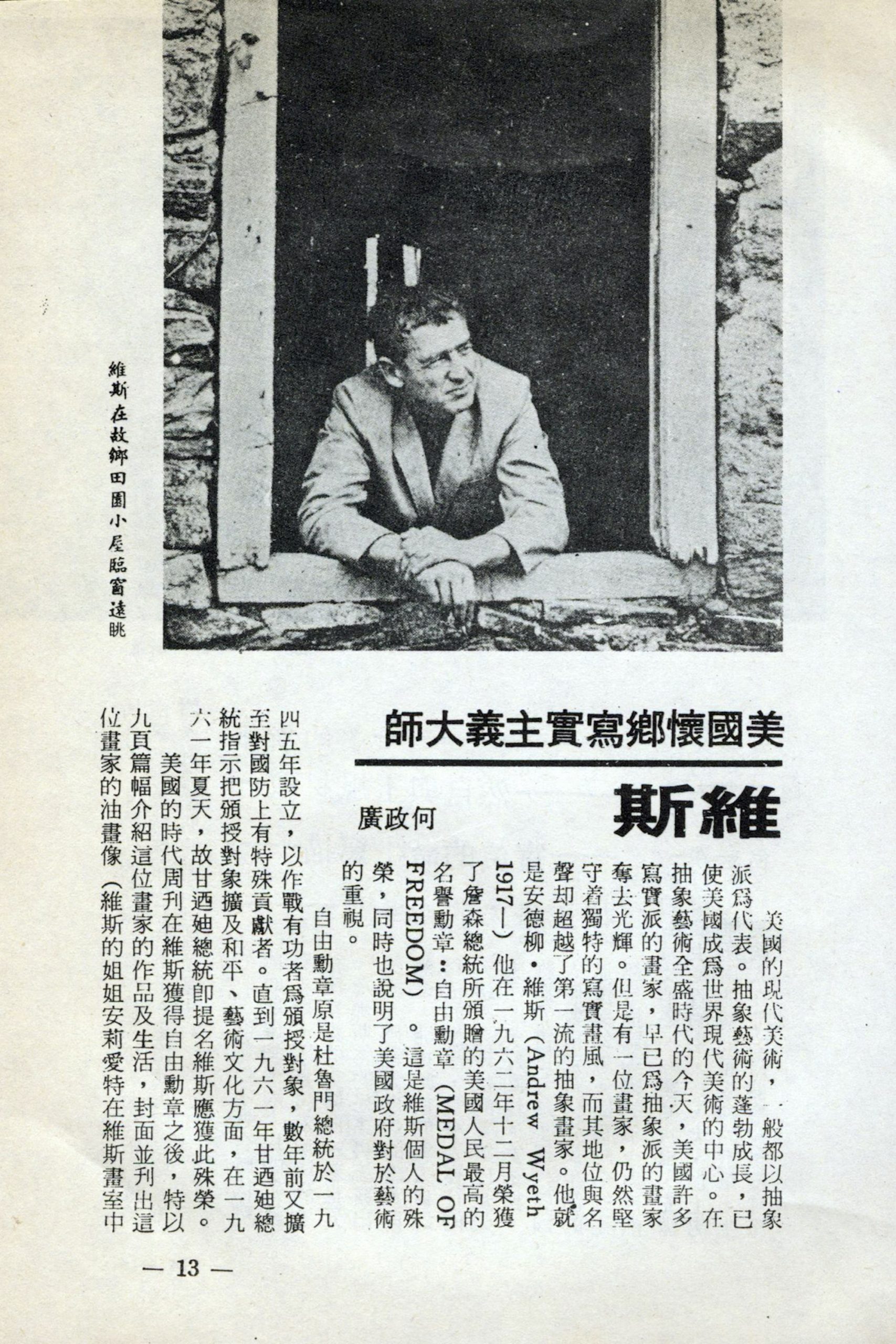

It was puzzling to see Andrew Wyeth as the featured artist in not one but two of Taiwan’s influential art magazines, both launched in the 1970s, during my research visits to the National Central Library in Taipei. The haze of jet lag from a transpacific flight, coupled with strained neuroreactivation of a native tongue, exacerbated my cognitive dissonance in reading the five-page encomium of Wyeth, in Chinese, in the inaugural issue of The Lion Art Monthly (雄獅美術), an influential trade magazine that began in March 1971 (fig. 1). Another archival dig led me to discover that Artist Magazine (藝術家), a long-running publication that started in June 1975, devoted nineteen pages in its second issue in a consideration of the artist: “Andrew Wyeth: America’s Most Famous Painter Today” (今日美國最著名画家魏斯) (fig. 2).1

That these Taiwanese magazines in effect vaulted over two decades of Abstract Expressionism/Pop/ Op/ Minimalism/ Conceptual Art and elevated a representational painter of the pre–World War II generation as the paragon of American art initially struck me as anachronistic. It goes against the received narratives of American modernism (or at least those that have been canonized) that emphasized postwar ascendency and valorization of American abstraction on the world stage as promoted through the US cultural diplomatic apparatus during the Cold War. The writers had not perhaps caught up with (or were reluctant to acknowledge) the new types of American art, I surmised—an admittedly judgmental speculation based on my experience of growing up in Taiwan and hearing about Taiwan being at least a decade or two behind Japan and especially the US in almost all aspects of modern life. (“If Japan could do it, why couldn’t we?” was a much-touted mantra meant to motivate local growth and development, for example.) But the choice of Wyeth—not Pollock, not Warhol—to represent the kind of American art that the publishers wished to highlight in the magazines to their burgeoning readership, almost three decades after the end of WWII, was indeed curious. Why Wyeth, in the early 1970s?

In his article for the inaugural issue of The Lion Art Monthly, “Wyeth: American Master of Nostalgic Realism” (美國懷鄉寫實主義大師), writer He Zheng-Guang (何政廣) acknowledged that with the postwar emergence and dominance of abstraction, representational painters had largely receded into relative obscurity.2 He argued that Wyeth was, however, an outlier whose reputation exceeded that of abstract painters even with his single-minded focus on creating realistic imagery. President Lyndon B. Johnson awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Wyeth in December 1963, He pointed out (but misidentified the year as 1962), and Time published a commemorative issue with a portrait of Wyeth (by his sister Henriette) on the cover and a nine-page tribute to Andrew Wyeth’s art. Such critical attention amply illustrated the personal accolades that the artist continued to receive, as well as the US government recognition of the national importance of art.3 More crucial, He posited that Americans continued to love and support Wyeth’s art, as they did with “the music of Dvořák [particularly his New World Symphony] and Foster,” because Wyeth expressed Americans’ collective admiration and appreciation for Nature, now infused with a nostalgia for the (supposed) “one-with-nature” life in the bygone era of Westward expansion. The artist’s vivid depictions of the enriching environment in the United States—“the earth’s many fragrances, the life cycles of the green grass, the renewing wind and sunny sky”—appealed to the emotional core within the “American soul,” He proposed.4

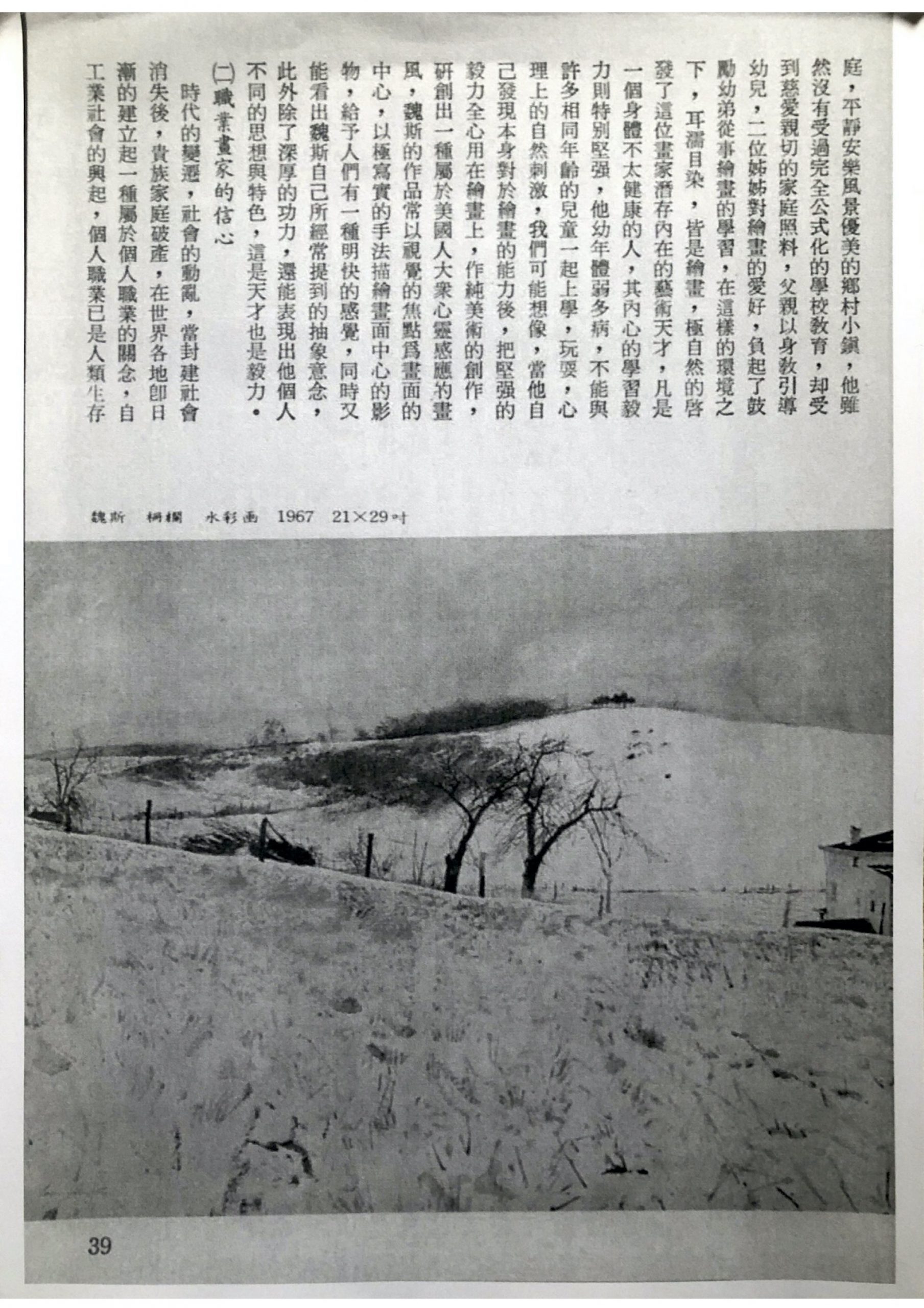

Fig. 3. Page showing Wyeth’s Fence Line (1967) in the Wyeth section, Artist Magazine, July 1975, p. 39

As I discovered on a separate research trip to Taiwan, He went on to found Artist Magazine in 1975 and was the force behind the publication devoting nineteen pages to surveying Wyeth’s oeuvre.5 He also published Wyeth: American Master of Nostalgic Realism in 1974, a book with a mixture of his own writings and those drawn or translated from sources in English. The magazine featured eighteen illustrations that included work by Wyeth’s father, N. C. Wyeth, and sister Henrietta, and also a translation of David McCord’s writing on Andrew Wyeth’s art—although there was no mention that the text was based on McCord’s introduction to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) catalogue for the 1970 Wyeth exhibition. It is unclear if this was an authorized reproduction and translation, but it appears that Artist Magazine’s choice of McCord’s writing likely had to do with Jiang Jien-Fei (蔣健飛), another contributor to the issue who oversaw the production and printing of the MFA’s exhibition catalogue.6

Jiang, a Chinese immigrant in New York, felt equipped to share his assessment of Wyeth, having spent considerable time examining and photographing about two hundred of Wyeth’s original artworks from the Boston exhibition. Jiang pointed out that Wyeth, who was an American artist unknown to most Taiwanese at the time, was justifiably called “the most famous American artist today” by Artist Magazine.7 In addition to acknowledging Wyeth’s artistic talent and dedication to painting, Jiang offered that Wyeth’s appeal and acclaim could be attributed to: 1) a prevalent nostalgia for the pre-industrialized United States, as depicted and preserved in Wyeth’s imagery (an assessment that echoed He’s); 2) the rise of an American middle class with discretionary money to purchase the kind of art they would understand and enjoy, such as Wyeth’s, for their homes; and 3) recognition of Wyeth’s imagery as “endogenously American” by a painter who kept his head down, his sight on his rural surroundings, and his focus on American subject matter (fig. 3). In short, Wyeth’s American art was realistic in style but thoroughly modern in concept and spirit—and was a model and inspiration for artists in Taiwan who struggled to shed the burden of Chinese painting traditions, as Jiang proposed, to find their place in society as contributing members who could help shape the cultural future of the nation.

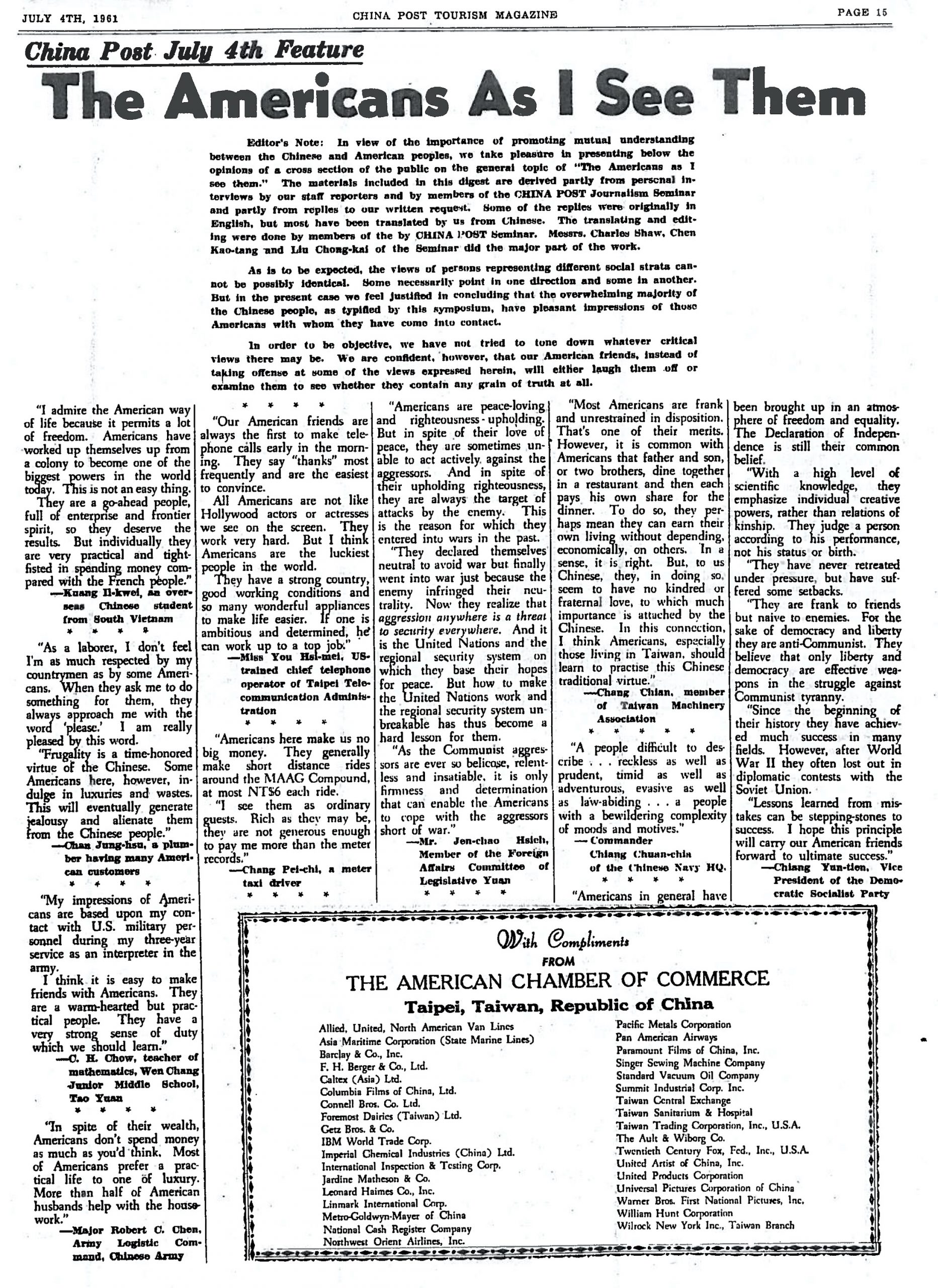

There was a generous dose of romanticism in both Jiang’s and He’s somewhat rosy generalization of Americans, likely meant to support their subjective affirmation of Wyeth’s artistic merit. As my archival research revealed, however, other Taiwanese held more varied and nuanced opinions about the United States and its people. For instance, a cursory look at comments in “The Americans as I See Them,” a 1961 survey of a “cross section of the public” conducted by China Post, Taiwan’s English-language newspaper, shows that the seventy-one Taiwanese respondents held divergent views of the Americans with whom they had interacted (fig. 4): “Most Americans are frank and unrestrained in disposition”; “Americans don’t follow a famous leader in order to establish themselves, or believe in fate. They stand on their own feet by exertion”; “Frugality is a time-honored virtue of the Chinese. Some Americans here, however, indulge in luxuries and wastes”; “Unlike those shown in the movies, the average American women lead a frugal and [D]iligent life. . . . I believe America owes its prosperity to its female citizens to a great extent”; “Rich as they may be, they are not generous enough to pay me more than the [taxi] meter records”; “With a high level of scientific knowledge, they emphasize individual creative powers, rather than relations of kinship”; “They seem to have no kindred or fraternal love, to which much importance is attached by the Chinese”; and “A people difficult to describe . . . reckless as well as prudent, timid as well as adventurous, evasive as well as law-abiding . . . a people with a bewildering complexity of moods and motives.”8 There is much more to parse in the dozens of comments published in the China Post Fourth of July feature than can be addressed here; suffice it to state that these observations show that Jiang’s and He’s romantic visions of the American collective nostalgia for a bygone era, vis-à-vis Wyeth, was hardly representative of the residents of Taiwan.

Fig. 5. Photograph showing the aftermath of the destroyed US Embassy in Taipei, 1957. Government Information Office, Executive Yuan, Taiwan

There was indeed ambivalent or outright anti-American sentiment undergirding the fraught relationship between the US diplomatic presence and Taiwanese residents. Many incidents illustrate that combustible tension, including the consequential “May 24 Incident” (五二四事件), or Liu Ziran incident (劉自然事件), in 1957—a geopolitical crisis that was omitted from the history textbooks with which I grew up during Taiwan’s martial law era (1949–87). On March 20, 1957, Robert G. Reynolds, an American army sergeant in the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) in Taiwan, fatally shot Liu Ziran twice with a .22 caliber gun because he accused Liu of spying on Reynolds’s wife in the bathroom at their duplex in Yangmingshan (陽明山). However, Liu’s body was found face down about two hundred feet from Reynolds’s residence, suggesting Reynolds’s active pursuit and intentional shooting, despite his legal team’s argument for his defensive act of neutralizing a perceived threat. The death of Liu, who was a clerk at the ruling Nationalist Party (國民黨, Kuomintang, or KMT) political school in the area, triggered investigations by both local and American authorities that led to contradictory conclusions, with the Republic of China (ROC) prosecutors refuting Reynolds’s self-defense claim against a “peeping Tom.” Owing to the MAAG Agreement, Reynolds enjoyed immunity from Chinese jurisdiction, and the case was taken over by the United States Embassy and the MAAG to be processed under US Military Code. He was tried on charges of voluntary manslaughter and was acquitted on May 23, two months after the killing. Local officials, the press, and the general public expressed shock and dismay, and their outrage was manifested in sustained protests that turned riotous, as demonstrators stormed the US Embassy and the US Information Service office in Taipei (USIS-Taipei), destroying furniture, equipment, and transportation (fig. 5).9 The US Embassy and USIS-Taipei had to operate with care in this highly volatile environment, as the agency was charged with managing and maintaining the US-ROC relations. USIS-Taipei also intensified efforts in promoting American culture and ideas to enhance so-called “cross-cultural understanding” (without acknowledging the uneven power dynamic between the two countries, of course) in order to ensure Taiwan’s cooperation in aiding US Cold War objectives.

This historical context led me to suspect that the choice of Wyeth as the American artist to introduce to their Taiwanese readers in the magazines was not based simply on the contributors’ idiosyncratic preferences. Indeed, in reading another article in the same issue, I spotted a fleeting mention of a film that the writer Liao Xiu-Ping (廖修平), a renowned printmaker, saw at USIS-Taipei. That led me to search for any corroborating reports in the press in 1975, and I found a China Times (中國時報) newspaper article, written by the same He Zheng-Guang, that discussed a public showing of a Wyeth film at the end of May of the same year.10 Furthermore, I found out that USIS-Taipei also staged a display of reproductions of Wyeth’s “masterpieces,” co-organized by Artist Magazine (founded by He), from December 23 to 29, 1975.11 This indicates that USIS-Taipei seized an opportunity to sustain the momentum and increase public awareness of Wyeth, as the film screening followed the release in late 1974 of He’s Wyeth book, and the exhibition followed Artist Magazine’s Wyeth features of June 1975. Such programming enabled USIS-Taipei to further promote the purported version of Wyeth’s Americanness (pastoral serenity, fulfillment from simplicity, embrace of a small community, and a sense of belonging, among other things) in effect to soften or offset the reality of the US military, political, and economic dominance over Taiwan. Such deployment of soft power in promoting American art and culture in foreign countries under the moniker of American democracy is illustrative of the US cultural diplomatic operations in Taiwan—the subject of my archival research in the first place.

“The Brush of Swords: US Cold War Cultural Diplomacy, American Art, and Taiwan’s Postcolonial Visuality,” as my project was initially titled, looks at the ambivalent relationship between US cultural diplomacy and the post-WWII identity formation of Taiwan, a small island off the southeastern coast of Mainland China to where the ROC government relocated in 1949, after being driven out by the emerging forces that formed the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Existing literature on Cold War cultural diplomacy has largely focused on US operations in Latin America and Eastern Europe but has overlooked Taiwan’s key role in the longstanding relations (and tensions) between the United States and the PRC. The US presidential visits in the postwar years, for instance—President Eisenhower in 1960 and Vice President Johnson in 1961—illustrate Taiwan’s geopolitical significance as a strategic vanguard in the US-led fight against communism along the Western Pacific Rim.12 As an Americanist, I am interested in investigating the scope and content of the kinds of curated visual translations of Americanism in different national and cultural contexts. In this case, I was curious to learn more about the promotion by the US government of “American ideals” through the deployment of “soft power”—specifically the arts, a “universally recognized means of cultural communication,” as a 1962 USIS memorandum states13—as a covert but critical way to help educate a nation-state struggling to establish its own identity after centuries of colonial rule by other nations, including as a Japanese colony between 1895 and 1945. By touting American arts, culture, sports, science, and technological advances as exemplary products of democracy through a series of USIS-sponsored programs, the United States aimed to guide Taiwanese postcolonial reconstruction and reinforce the US-ROC alliance in order to secure the island’s strategic value for US Cold War battles. More important, I wanted to study the local reception of and reaction to such cultural encounters and, to a certain extent, programmed (propagandistic) imports by comparing the objectives of leaders in Washington, DC, to those of Taiwanese artists, intelligentsia, and the press response in order to understand the fluid, nuanced, and often fraught ways in which mutual cooperation and implicit coercion occurred on the ground in this type of cultural diplomacy and exchange.

This kind of cross-cultural and international research calls for examining historical documents in both Mandarin Chinese and English, a task with challenges that one might not anticipate in this digital age—although not unfamiliar to art historians who conduct archival research in person. Old Taiwanese newspapers are mostly accessible only at libraries and archives in Taiwan, the most comprehensive of which are the National Library databases in Taipei. Initially, I struggled with even the basics—such as figuring out how to toggle between two languages at the library computer stations, in addition to learning how to navigate different indexing/search logic and systems in Taiwan—because my training as an art historian has been entirely in English and in the United States. (If only I could have captured the looks of those patient but visibly puzzled librarians staring back at a clueless adult who acted as if he were visiting a library for the first time.) I was disappointed to confirm, after months of research, that almost none of the USIS-Taipei memos and archives from the post-WWII decades remain in Taiwan due to geopolitical changes. The United Nations General Assembly voted to admit the PRC in 1971, resulting in the ROC’s exit—or “expulsion,” depending on which school of interpretation one accepts—from the UN. President Nixon visited mainland China in 1972, a landmark trip that eventually led to the Carter administration’s official recognition of the PRC as the one nation of China and therefore severed the US-ROC diplomatic ties on January 1, 1979.14 As the US State Department withdrew operations from Taiwan, the USIS memos also left the island, save for some microfilms containing “Confidential US State Department Central Files” on China from the late 1940s at Academia Sinica, Taiwan’s national academy for research. Seeing the USIS-Taipei documents required a series of long visits to the National Archives in College Park, Maryland, another place designed to make one feel clueless and overwhelmed by the sheer size and complexity of the system/database—and by the not-so-friendly staff who made a daily sport of scolding researchers, be it during my first foray into the archives in 2009 or my most recent one a decade later. Nevertheless, with the aid of some helpful archivists, I was able to examine voluminous documents outlining USIS-Taipei’s daily operations, which in turn enabled me to reconstruct a better (but far from comprehensive) sketch of those Cold War years.

It is worth noting that these domestic and transpacific travels led to progressively deeper and more relevant findings, and each discovery builds on the previous excavation. Any single trip almost never results in a smoking-gun revelation that then completes one’s research; therefore, sustained funding for this type of multiyear art-historical research is essential.15 Without adequate support, I would not have been able to return to those Taiwanese archives to examine the earliest issues of Artist Magazine in which, for example, I discovered that its founder, He Zheng-Guang, turned out to be the writer for the Wyeth article in the earlier Lion Art Monthly. My visits yielded findings that helped contextualize the two features on Wyeth in two burgeoning Taiwanese art magazines, along with the release of He’s Wyeth book, and the USIS-Taipei film screening and exhibition of Wyeth’s art, within the watershed decade of dramatic changes in Taiwan’s standing on the world stage. Wyeth’s art (and Wyeth himself) had come to “represent middle-class values and ideals that modernism claimed to reject,” as Michael Kimmelman wrote in Wyeth’s New York Times obituary in 2009.16 My discovery of these Taiwanese articles demonstrates that Wyeth’s predominantly rural American subject matter made him an appealing model for Taiwanese artists (at least according to the art magazine contributors) who lived in a predominantly agricultural economy, at a time when their country was rebuilding its postcolonial identity. The proclamation of Wyeth as “America’s most famous painter today”—at least in Taiwan in the 1970s—points to the perhaps unexpected geopolitical significance of this canonical artist in the context of Cold War Asia that merits further exploration.

Cite this article: ShiPu Wang, “Wyeth in Taiwan,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10553.

Notes

- He Zheng-Guang, “Wyeth: Master of American Nostalgic Realism,” The Lion Art Monthly 1 (March 1, 1971): 13–17; Artist Magazine 2 (July 1975): 20–30 and 36–44. ↵

- He, “Wyeth: Master of American Nostalgic Realism,” 13–17. ↵

- He misidentified the year for Wyeth’s Presidential Medal, which was awarded in 1963, the same month Time published the cover and feature. “Andrew Wyeth’s World,” Time 82, no. 26 (December 27, 1963): 44–52. ↵

- He, “Wyeth,” 14. ↵

- I looked into the archives of this magazine at the suggestion of Jason C. Kuo, professor of Chinese art and author of pioneering literature on postwar Taiwanese art at the University of Maryland, College Park; see, for example, Kuo’s “Decolonization, and Cultural Politics in Postwar Taiwan,” Arrs Orientalis 25 (1995): 73–84. ↵

- Frederick A. Sweet, Andrew Wyeth, exh. cat. (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1970); David McCord, “Wyeth’s World,” trans. Zhong Shing-Xian, Artist Magazine, no. 2 (July 1975): 26–30. ↵

- Jiang Jien-Fei, “A Chinese’s Perspective on Wyeth’s Success,” Artist Magazine 2 (July 1975): 38–43. Jiang had a career in the print industry and was the second son of Jiang Yi (also Chiang Yee), a Chinese poet/author/painter/calligrapher who taught at Columbia University (1955–77), “Jiang Yi Achievement Seminar,” The Renwen Society at China Institute, accessed September 9, 2020, http://www.chineselectures.org/102007.html. ↵

- “The Americans As I See Them,” China Post Tourism Magazine, July 4, 1961, 15–19. Respondents ranged from government officials, military personnel, and politicians, to teachers, students, and taxi drivers. ↵

- For accounts and analyses of the incident and its legacy, see Li Kuo-Cheng, “1957 Taipei Liu Ziran Incident and the Signing of the 1965 Status of U.S. Forces in Taiwan Agreement” (1957 年台北「劉自然事件」及 1965 年<美軍在華地位協定>之簽訂), Soochow Journal of Political Science (東吳政治學報) 24 (December 2006): 1–68; Stephen G. Craft, American Justice in Taiwan, The 1957 Riots and Cold War Foreign Policy (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2016); and Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955–1957, vol. 3, China, eds. Harriet D. Schwar and Louis J. Smith (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1986), 524–25, 533, 539, 541. ↵

- He Zheng-Guang, “Another Side of America: Thoughts on the Wyeth Art Film,” China Times, June 19, 1975, 7. Liao Xiu-Ping, “Regarding Hyperrealism in Relation to Wyeth’s Paintings” (從魏斯的繪畫談到超寫實主義), Artist Magazine 2 (July 1975): 36–37. The question of what that film was remains unanswered. Karen Baumgartner at the Andrew Wyeth Office, Brandywine River Museum of Art, suggested that the film might be The World of Andrew Wyeth, produced by ABC-TV, Schwartz-Wallace Productions in 1967. Correspondence with author, December 30, 2019. Thanks to Baumgartner and David Cateforis of the University of Kansas for answering my inquiries. ↵

- “USIS Showed Wyeth Masterpieces,” China Times, December 23, 1975, 5. I was unable to find photographs in newspapers that showed what Wyeth works were reproduced; the US National Archives may hold memos and visual records that I have not had the chance to search and uncover due to COVID 19–related disruptions of research activities that many colleagues have also faced. ↵

- Literature abounds in this area of study; for overviews written in English, see Hung Chien-Chao, A History of Taiwan (Reimini: Il Cerchio, 2000); Marshall Green, Evolution of US-China Policy, 1956–1973: Memoirs of an Insider (Arlington: The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project, 1998); and George H. Kerr, Formosa Betrayed (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965), among many others. ↵

- USIS-Taipei to USIA Washington Memo, “Painting Exhibition by Liao Chi-chun and Shiy De-jinn,” June 12, 1962, 3, National Archives TW-3-61, RG 306, TW 1-61, Box 90. ↵

- Chris Horton’s “Taiwan’s Status Is a Geopolitical Absurdity” in The Atlantic (July 8, 2019) offers a cogent and accessible summary of the U.S.-ROC-PRC history and issues: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/07/taiwans-status-geopolitical-absurdity/593371. ↵

- I am grateful for the support from the Terra Foundation for American Art, the University of California Pacific Rim Research Program, and the Academic Senate and the Center for the Humanities at the University of California, Merced, over the past decade. ↵

- Michael Kimmelman, “Andrew Wyeth, Painter, Dies at 91,” New York Times, January 16, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/17/arts/design/17wyeth.html. ↵

About the Author(s): ShiPu Wang is Professor of Art History and Coats Endowed Chair in the Arts at the University of California, Merced