The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison

Curated by: Milwaukee Art Museum

Exhibition schedule: Milwaukee Art Museum, October 18, 2018–March 10, 2019

More than thirty years after the publication of “The Body and the Archive,” by Allan Sekula, it remains one of the classic essays in the history of photography. It traces the use of photography in the nascent fields of criminology and sociology in the nineteenth century.1 French police bureaucrat Alphonse Bertillon, for example, utilized the instrumental potential of photography to measure and describe the criminal body in a standardized manner and place it within “a comprehensive, statistically based filing system”—in other words, an archive.2 With the exception of its quantifiable visual characteristics, the photographed criminal body remains mute, unable to respond to the archive in which it has been positioned.3 In general, people who serve time in prison or jail today remain subject to the repressive instrumental function of photography and often find themselves as voiceless as those whose images appeared in Bertillon’s massive filing cabinets, reduced to a series of statistics and powerless to speak about their incarcerated status.

The exhibition The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison challenges the historically repressive relationship of photography to the bodies of incarcerated men. The voices of the men, through their written and spoken words, are prominently on display in this presentation. Instead of being photographed and reduced to quantifiable statistics, the men of San Quentin State Prison are the ones who do the looking and writing about photographs, some of which come from the historical archives of the institution where they are serving time. The photographs and the men’s writings on them—in both the figurative and literal senses—are the primary visual objects of the exhibition. By highlighting the responses and analyses produced by the men instead of the standardized institutional images produced of them, Poor’s San Quentin Project and its public debut at the Milwaukee Art Museum force a reevaluation of the purely instrumental function of photography within the criminal justice system.

In 2011, Nigel Poor (b. 1963), a Bay Area artist and professor at California State University, Sacramento, began teaching history of photography classes at San Quentin State Prison in Marin County as part of the Prison University Project. Poor needed to figure out how to teach the history of photography to her students without the usual tools of her discipline; the men were not allowed to have cameras and they were not able to regularly view images for formal analysis in person or online. Poor arrived at a pedagogical solution to this lack of resources through an exercise she called “Image Mapping.” She distributed 11 by 17-inch sheets of paper with an inkjet reproduction of the photographs printed in the center of the sheet (with generous margins) that she wanted the students to analyze. The photographs she selected, by artists William Eggleston, Lee Friedlander, Abelardo Morell, and Hiroshi Sugimoto, among others, are canonical to scholars of contemporary art photography but were not likely to be familiar to the men of San Quentin.

Fig. 1. A visitor looks at Nigel Poor and Frankie Smith, Mapping Joel Sternfeld, 2011–12, inkjet print, with ink notations, 11 x 17 in. The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison, Milwaukee Art Museum; photography by the author

Poor’s students worked on the same photograph continuously over the course of about one month. On one side, they wrote extensive notes about the visual content of the image, attending to the larger cultural contexts as well as the many small details captured by the camera. They often added circles, arrows, and other marks to highlight specific objects within the image, creating in some cases an intricate overlay of visual information on the photographs. This exercise was a central part of learning how to read photography as a visual medium. According to Poor, “each image is like a crime scene to be studied, written on, and mapped to reveal its undisclosed story.”4 On the other sides of the reproductions, the students recorded their personal responses to the photographs, including the meanings and narratives they discerned by mapping the images, and by looking slowly and deliberately.

The principal visual documents featured in the first gallery of the exhibition are six of the 11 by 17-inch sheets of paper that Poor’s students looked at, inscribed, drew on, and “live[d] with” as part of the class.5 The sheets of paper used in the image-mapping exercise are double sided, so the museum employs an inventive installation strategy that enables visitors to read both sides of the students’ extended analyses. The mapped reproductions are displayed between two pieces of acrylic, suspended from the ceiling by two strands of clear filament at museum standard eye level, arranged in a broad circle (fig. 1). The mapping notes are presented along the outside of the circle, and the personal responses are on the inside. Wall text several yards away lists Poor and the individual who mapped the image, along with a standardized title, “Mapping [photographer’s name],” as a way to both credit the artist and inform exhibition visitors about the sources of both the notations and the reproduced images.

Fig. 2.Installation view of the Image Mapping section of the exhibition The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison, Milwaukee Art Museum; photography by the author

A large circle in a warm brown shade demarcates the installation space on the floor below the six sheets of paper suspended in acrylic (fig. 2). The preparatory department staff of the Milwaukee Art Museum likely knew that this circle would serve as a subtle signal to prevent visitors from wandering into the hanging acrylic. More central to the themes of the exhibition, however, is the way in which one is required to traverse this circle to read the writing on both sides of the sheets, repeatedly moving in and out of the ring of images. This makes a visitor more conscious of the freedom to move effortlessly between the two spaces, in stark contrast to the incarcerated men whose thoughts and ideas are on exhibition.

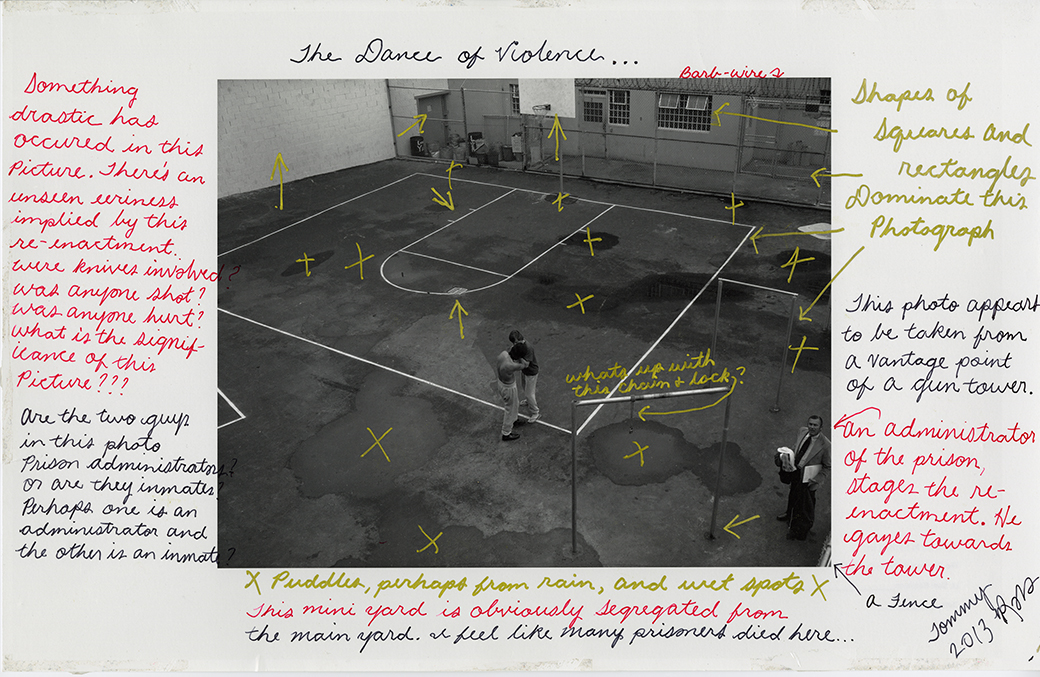

“Archive Mapping,” the second part of the San Quentin Project, is installed in the next gallery of the exhibition. The basic instructions for the exercise remain the same as the Image Mapping prompt, but the photographs the men analyze are much more specific to their lives in San Quentin State Prison. In 2012, Poor was granted access to the prison’s historical archive, which held thousands of 4 by 5-inch negatives. The black-and-white images were taken by corrections officers, mostly in the 1960s and 1970s, often for use as visual evidence of an event inside the prison. Although the archival photographs occasionally show the aftermath of violent incidents, they also document banal activities and even celebrations such as Mother’s Day visits and prison weddings. Overall, they present scenes that register strongly with the men’s lived experiences in San Quentin today. Their familiarity with the environment and culture of the prison make their written notes on the images both informed and powerfully moving. As Poor notes on her website, the function of the archival images as evidence depends on “the assumption that photography speaks the truth, that it has an unquestionable veracity.” 6 By inscribing them with notes that reflect their subjective experiences of the prison, however, the men intervene in the archive and imprint their own histories and memories onto the photographs, uncoupling them from their solely evidentiary function (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Nigel Poor and Tommy Shakur Ross, Re-Creation, 1–6–75, 2013, inkjet print, with ink notations, 11 x 17 in. Courtesy of Nigel Poor, with thanks to the Prison University Project, Warden Ron Davis, and Lieutenant Sam Robinson

As with the art photographs in the first gallery, Poor printed the images on sheets of paper for the men to use in the visual analysis exercise. Instead of displaying the sheets with the images and the men’s writing encased and suspended from the ceiling, in this gallery, they are framed and installed along the wall in a long, tightly spaced row. Each document is again identified by wall text with Poor’s name and the name of the individual who mapped the image, as well as a descriptive title and date drawn from the prison archive. Across the room, on the opposite walls, are gelatin silver prints, some of them printed from the same negatives as the Archive Mapping documents. These photographs are also hung in a dense row, but without inscriptions or separate identifying information. This second set of images gestures toward another element of Poor’s San Quentin Project, which she calls “Archive Typologies.” For this part of her social practice, Poor attempts to place the thousands of archival images found in San Quentin into one of twelve subject categories she created, such as “Escape and Confinement” and “Injury and Repair.”7 Unlike the collaborative efforts required of the Image Mapping and Archives Mapping components of her project, Poor approaches the work of Archive Typologies alone. Her goal for this classification project is “to deal with the archive itself, to study the images and hope that answers will be revealed.”8 In a project not unlike Bertillon’s methodology in nineteenth-century Paris, although completely contrary in its objectives, Poor is attempting to find a kind of logic in the massive amount of visual data that the photographic archive provides about the men of San Quentin. Furthermore, the loosely mirrored walls of photographs in the second gallery of the exhibition, some visually mapped and thoughtfully inscribed, others left to present their seemingly evidentiary visual information without subjective commentary, offer insight into Poor’s reflections on the power of the photographic archive and the crucial work her project performs in amplifying the voices of the incarcerated men.

The third and final gallery of the exhibition offers the most literal example of giving voice to the incarcerated men of San Quentin, done in a uniquely twenty-first–century medium: the podcast. Bright green walls (the walls of the other galleries are a combination of neutral browns and white-onwhite cube) and a cluster of armchairs around a central listening station indicate the abrupt change in the tone of the exhibition. This gallery is devoted to Ear Hustle, a podcast produced by two men incarcerated at San Quentin, Earlonne Woods and Antwan Williams, with Nigel Poor.9 The podcast serves as a “platform for the incarcerated men to share their own complex and nuanced stories with a broad audience.”10 Visitors can listen to a selection of episodes from the three seasons of Ear Hustle (named after a prison term for eavesdropping), browse a library of recent books on the criminal justice system, and view video clips of Woods, Williams, and Poor recording episodes of the podcast with other men from San Quentin.

In the exhibition, The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison, the voices of the incarcerated men are featured front and center. No longer reduced to mute subjects of the photographic archive, they respond vigorously and thoughtfully to their environment and the events around them. The exhibition ends with words about the project from Tommy Shakur, one of the men of San Quentin: “This has exceeded any expectations that I ever had about the archive project. I’m interested to know how our works impact others. In other words, what do the viewers think about our works at the museum?”11 Shakur’s question, addressed directly to the exhibition visitors, suggests the necessary next step in Poor’s social practice project: more than just listening to their voices, a conversation needs to be started with the men of San Quentin.

Cite this article: Beth A. Zinsli, review of The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison, Milwaukee Art Museum, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1707.

PDF: Zinsli, review of The San Quentin Project

Notes

- Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (Winter 1986): 3–64. ↵

- Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 18. ↵

- Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” 10. ↵

- Wall text, The San Quentin Project: Nigel Poor and the Men of San Quentin State Prison, Milwaukee Art Museum, October 18, 2018–March 10, 2019. ↵

- Nigel Poor, “San Quentin Project Part #1 Mapping,” accessed February 11, 2019, http://nigelpoor.com/project/san-quentin-part-1. ↵

- Nigel Poor, “San Quentin Project Part #2 Archive Images,” accessed February 11, 2019, http://nigelpoor.com/project/san-quentin-part-2. ↵

- Nigel Poor, “San Quentin Project Part #3 Archive Typologies,” accessed February 11, 2019, http://nigelpoor.com/project/san-quentin-part-3. ↵

- Poor, “San Quentin Project Part #3.” ↵

- Nigel Poor, Earlonne Woods, and Antwan Williams, “Ear Hustle,” accessed March 10, 2019, https://www.earhustlesq.com. ↵

- Wall text, The San Quentin Project. ↵

- Wall text, The San Quentin Project. There was a small touchscreen device installed near the exit of the exhibition with the prompt “What do you think about these works and does it change your perception to see them on view at a museum? Please share your thoughts so we can share them with the men of San Quentin.” Responses could be typed into a text box and submitted, though it was not stated how or when the men would receive the submissions from visitors. ↵

About the Author(s): Beth A. Zinsli is Curator and Assistant Professor of Art History at Lawrence University