Kerry James Marshall: Mastry

Curated by: Helen Molesworth, Dieter Roelstraete, and Ian Alteveer

Exhibition schedule: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, April 23–September 25, 2016; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, October 25, 2016–January 29, 2017; and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, March 12–July 2, 2017

Exhibition catalogue: Ian Alteveer, Helen Molesworth, Dieter Roelstraete, and Lanka Tattersall, Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, exh. cat. Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; New York: Skira Rizzoli Publications, 2016. 280 pp.; 119 illus. (mostly color). Hardcover $65.00 (ISBN: 9780847848331)

Fig. 1. Installation view, Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, The Met Breuer, New York.

October 25, 2016–January 29, 2017. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Chicago-based artist Kerry James Marshall (b. 1955) has been frank about “making pictures that aim to make their way into museums.”1 And enter museums they have. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles have jointly organized Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, the largest museum retrospective of his career to date. In New York, the stunning exhibition occupied two floors of the Marcel Breuer building, now The Met Breuer, a mid-century landmark whose material bluntness is bound up in the same ideologies of social reform as the public housing developments in Marshall’s Garden Project series. The artist’s vision for change originates in a desire to contest the very organizing principles of modernism around which such ideologies (and civic institutions) formed. Marshall reminds us that artists of color have historically endured a conditional access that reinforces the narrative of their own exclusion: “So it’s like all of the black folks who achieve this sort of mythic status as artists are always people who were working as naives, untrained, kind of natural artists.”2

As he articulates it in his catalogue essay, the false promise of abstraction meant that those looking to escape “racial readings” of their artwork suffered the indignity and diminution of belatedness.3

For all of these reasons, Marshall has committed himself to figuration, and more specifically, to the representation of blackness. It is, as exhibition curator Helen Molesworth argues persuasively in the publication, an institutional critique that has escaped notice as such because of his supremely traditional means. The temptation to read Marshall’s work art historically is inescapable—you encounter the mirrored service economy of Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies–Bergère, vernacular riffs on the elite confections of Florine Stettheimer, and the pathos of Cy Twombly’s roses—but these grand citations can sometimes blind audiences to more subtle operations. For example, a fixation on canonical influences may supplant a discussion of African diasporic aesthetics, as more than one critic has noted. It also risks deescalating the urgency of the work, something about which there is significantly more to say.

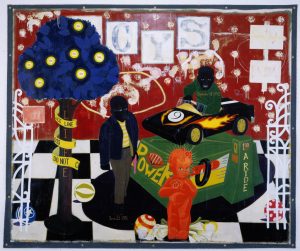

Fig. 2. Kerry James Marshall, The Lost Boys, 1993. Mixed media on canvas; 109 x 120 in. ©Kerry James Marshall; Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Featuring nearly eighty works in total, the exhibition begins with two canvases from 1993, a tidal year for Marshall since he transitioned to the prodigious scale for which he has become known. Together, The Lost Boys (Collection of Rick and Jolanda Hunting) and De Style (Los Angeles County Museum of Art) telegraph the artist’s simultaneous attentions to structural racism—young African American men cyclically lost to drugs, incarceration, violence—and spaces such as the barbershop, a site of community and cultural empowerment. As the curators must recognize, The Lost Boys primes audiences for Marshall’s allusive dexterity. Here police tape snakes up the trunk of a tree of life, a species whose pernicious fruit contains bullets at the core. Bubblegum pink toy gun in hand, one young boy strides past another who enjoys a supermarket ride, and the artist assigns ominous dates to each. At top right, the letters “POW” appear, evoking both the onomatopoetic sounds of comic book brawling and the more sobering designation for a prisoner of war.

On the other hand, in De Style, Marshall depicts survivors. He associates the aesthetic—and therefore political—self-determination of Percy’s House of Style with De Stijl, an early twentieth-century avant-garde movement. As one of the essayists astutely points out, he even smuggles in reference to Dutch geometric abstraction in the primary colors of the workstation.4 That one prominent art critic’s review frames Marshall’s retrospective as “not an appeal for progress in race relations but a ratification of advances already made” is somewhat bewildering in the face of this opening gambit.5 After all, both of these paintings date from the year after the 1992 acquittal of Los Angeles police officers in the beating of Rodney King and the ensuing waves of unrest. Surely, this pairing—front and center with the introductory wall text—appeals for some acknowledgment of the malevolence and tenacity of institutionalized violence?

Fig. 3. Kerry James Marshall, De Style, 1993. Mixed media on canvas; 109 x 120 in. ©Kerry James Marshall; Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Elsewhere in the show, the racial politics of Marshall’s practice are equally overt. In They Know that I Know (1992; Anonymous), for instance, he presents an alternative creation narrative. A black couple in carnal embrace reclines beneath trees bearing racial and ethnic classifications, their canopies abloom with Harlequin romance novel covers. At the far right, one ebonized and particularly attenuated stalk designated as “negroid” evinces none of this fecundity. Its growth seemingly arrested (a daub of paint runs suggestively from a cleft branch), this tree is inhospitable, if not dead, and the birds land elsewhere. Yet Marshall chromatically conjoins the couple’s feet to this trunk, making them the roots of a barren tree.

More recently, his Still-Life with Wedding Portrait (2015; Collection of Jay and Gretchen Jordan) casts an African American as an elite but nevertheless manual laborer, something relatively unusual in Marshall’s oeuvre. Here the artist presents a portrait of abolitionist Harriet Tubman with her first husband, John, to whom she was married from 1844 to 1851. His hands rest tenderly on her shoulders, his epaulet-like fingernails, perhaps a reference to her nickname —“General Tubman”—rhyme visually with the buttons down the front of her dress. This thematics of touch is echoed in the actions of the art handlers balancing the canvas, but with crucial differences. With one hand on each corner, they act to level the painting within the painting, but within Marshall’s greater composition, their presence only introduces asymmetries and inversions. Unlike the Tubmans, the installers wear gloves, mediating their physical contact. The figure at right wears one white and one black glove—the latter interpreted in a catalogue entry as reminiscent of the raised fists of Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the 1968 Olympics —and we see beneath them the exposed wrists of an African American. White cotton gloves conceal the race of the other individual, and this indeterminacy throws the painting into greater precarity. What appeared to be a painting about the stabilization of a painting instead becomes an allegory of disallowance and insecurity, with touch charged and denied, and racial identifiers mismatched, displaced, and altogether confounded. Simply put, this still life is anything but still.

Fig. 4. Kerry James Marshall, Marriage Portrait of Harriet and John Tubman, 2015. Acrylic on PVC panel; 59 ½ x 47 ½ in. ©Kerry James Marshall; Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Unfortunately I missed seeing the exhibition in Chicago, but it is almost impossible to visualize a space better suited to its presentation than The Met Breuer. On the second floor of the exhibition, curators and designers pushed back the walls outside of the elevators, creating what amounted to a deep and semi-enclosed courtyard. They shrewdly installed this exterior-feeling space with Marshall’s Garden Project paintings, a series depicting public housing, but with a twist. Here he balances an acknowledgment of the fraught history of these developments, embodiments of segregationist policies and symbols of urban blight, with glimpses of their promise fulfilled. From this gallery, where the unusually long sightlines complement the subject matter, one rounds a corner into a comparatively claustrophobic room installed with Marshall’s Mementos and Souvenirs. By and large, Marshall stages these reflections on the Civil Rights movement in domestic interiors, and this transition from the grounds of public housing projects into private homes proves jarring. Once again, the sensitive exhibition design adapts to its contents, and the confinement of this gallery evokes the suffocation of mourning, but also, perhaps, the retrenchment felt by those who saw so many individuals martyred for the cause.

Each time I visited the exhibition, it teemed with people, many of them maneuvering through the crowd with companions, as determined units. Marshall’s baroque tableaus invite close looking, but they also induce immediate comment. Even when parsing them collaboratively, it is easier to cache observations than to piece them together. For the work exhibits a paratactic logic—pictorial facts coexist alongside one another peaceably, but they remain self-contained and refractory, refusing to resolve. In the tautly and, for the most part, plausibly constructed De Style, Marshall embeds an anecdotal detail so incongruous that it warps the rest of the composition. Where we expect to see a calendar illustration on the rear wall we instead behold what looks like a photocopied diagram of a uterus (a reproduction, in other words). Ever recursive, Marshall incorporates this motif into at least two other works in the exhibition: Beauty Examined (1993; Collection of Charles Sims and Nancy Adams-Sims) and So This is What You Want? (1992; Collection of Daryl Gerber Stokols and Jeffery M. Stokols). Whereas there it participates in the heterogeneity of the collage conceit, in De Style, it insinuates itself into the illusion, if only to rupture it. Does the sly inclusion of this gynecological image—a cipher for sexual politics—destabilize, perhaps even radicalize this genre scene? Or does it incite nothing of the sort? The beauty of Marshall’s body of work is that we cannot say for certain and it is a credit to the curators and catalogue contributors alike that they honor this irresolution by refraining from excessive iconographic decoding.

What this retrospective reveals is Marshall’s investment in representing the fullest expression of African American subjectivity, itself a political gesture. Whether portraying a historical figure, such as Nat Turner or Harriet Tubman, or an everyman or woman, Marshall imbues his subjects with private desires without making them entirely legible to us. He paints many of these individuals not at work, but at leisure, all too aware of how recreation carries racial and class markers. Even at the barbershop or the beauty parlor, labor passes for sociability. And what public space materializes the stakes of leisure more than the museum? It is a cultural site that is nominally democratic but often prohibitively costly, with tiered access to guarantee that its constituent populations rarely mingle. Mastry demonstrates that Marshall’s pursuit of art historical restitution within the museum belongs to a larger campaign for social justice.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1600

- Victoria L. Valentine, “‘The Figure Remains Essentially Black in Every Circumstance’: Kerry James Marshall Previews His Master Paintings at MCA Chicago,” Culture Type, May 2, 2016, accessed on February 13, 2017, http://www.culturetype.com/2016 /05/02/the-figure-remains-essentially-black-in-every-circumstance-kerry-james-marshall-previews-his-master-paintings-at-mca-chicago/. ↵

- Oral history interview with Kerry James Marshall, August 8, 2008. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Available at https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-kerry-james-marshall-13706. ↵

- Kerry James Marshall, “Shall I Compare Thee . . . ?” in Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, exh. cat. (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago; New York: Skira Rizzoli Publications, 2016), 73. ↵

- Lanka Tattersall, “Black Lives, Matter,” in Kerry James Marshall: Mastry, 65. ↵

- Peter Schjeldahl, “Kerry James Marshall’s America,” The New Yorker, November 7, 2016, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/11/07/kerry-james-marshalls-america. ↵

About the Author(s): Diana Tuite is the Katz Curator at the Colby College Museum of Art