Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965–1975

Curated by: Melissa Ho

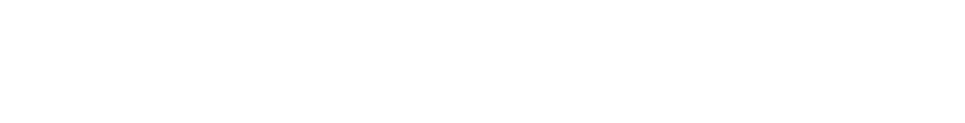

Fig. 1. John Lennon and Yoko Ono, WAR IS OVER! IF YOU WANT IT, 1969. Offset lithograph, 30 x 20 in. Courtesy of Yoko Ono Lennon

Exhibition schedule: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC: March 15 –August 18, 2019; Minneapolis Institute of Art, MN: September 28, 2019–January 5, 2020

Exhibition catalogue: Melissa Ho, ed., Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965–1975, exh. cat., with essays by Melissa Ho, Thomas Crow, Erica Levin, Katherine Markoski, Mignon Nixon, and Martha Rosler and contributions by Robert Cozzolino, Joe Madura, Sarah Newman, and E. Carmen Ramos. Washington, DC: Smithsonian American Art Museum in association with Princeton University Press, 2019. 416 pp.; 171 color illus.; 107 b/w illus. Cloth $65.00 (ISBN: 97806911911188)

As the title indicates, this outstanding exhibition curated by Melissa Ho for the Smithsonian American Art Museum focuses on the responses of individual American artists in their real time to the armed conflict in Vietnam. As we might imagine, these responses took the form of outrage, indignation, horror, sadness, and grief—but also wit, as the show abundantly demonstrates (fig. 1). Numerous media are featured: painting, drawing, sculpture, graphics, photography, collage, an environmental installation, and video, performance, and conceptual works., executed in a diversity of styles, including traditional, modern, postmodern, and agitprop. While all this variety might suggest a disorderly exhibition, a hodgepodge, or grab-all, it is instead splendidly disciplined and thoughtfully organized.

It is not a backward-looking exhibition. It panders neither to baby boomer nostalgia nor the yearning of millennials for a useable past to be found in the antiwar generation of their parents or grandparents. No lava lamps on display, no audio mixes of Janis, Jim, Jimi, and Bob, and no heavy-handed connections spelled out between those tumultuous times and our own. The connections are there, certainly, but the viewer is not steered into making them.

This is serious business, even when clever, witty, and fun. Take, for example, the 1968 Minimalist steel sculpture by Barnett Newman, Lace Curtain for Mayor Daley. Newman, the famed first-generation Abstract Expressionist and Color Field painter, was not known for his occasional forays into sculpture, and certainly not for his sense of humor. Nonetheless, this six-foot-high steel bedframe encasing a grid of galvanized barbed wire—seven vertical strands crossed laterally by eleven shorter ones—impishly conjures up the barbed-wire barriers affixed to the front of army jeeps for crowd control during the 1968 Chicago riots. But that is not its only level of humor. As Robert Cozzolino points out, the title of the work jeeringly alludes to the parvenu pretentions of formerly working class (“lace-curtain Irish”) Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley.1 The steel construct also mocks, more gently, the relatively apolitical aspirations of Minimalist sculpture and the Procrustean confinements of the modernist grid.

Fig. 2. Martha Rosler, Red Stripe Kitchen, from the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, c. 1967–72. Photomontage, 24 x 20 in. The Art Institute of Chicago, through prior gift of Adeline Yates; exhibition copy provided by Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

Less conceptual and abstract than Newman’s barbed-wire bedframe and more immediate in its punch is Martha Rosler’s House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967–72), a portfolio of framed photomontages that bristles with aggressive black humor. Rosler cut pages from mass-media publications, most notably the furniture and decor magazine House Beautiful, and collaged onto them photojournalistic images of the war or other contemporary sites of violence. Red Stripe Kitchen (fig. 2), for example, introduces two American combat soldiers into a staged, up-to-the-minute consumer paradise with white walls, white counters, wicker-topped stools, matching red cups, bowls, and plates, and, on the far wall, a swooshing red stripe. Wrenched from their original context, the soldiers stoop over as if searching for booby traps in a Vietnamese hut; only here, it is a pristine American kitchen.

Another in the series, Balloons, so called because of the multicolored rubber balls artfully piled up in the corner of a stylish, two-story American living room, inserts into the foreground a Vietnamese mother carrying a bloodied baby in her arms. The viewer experiences sickening cognitive dissonance: the moral distance between the opulent setting of the photomontage and its grief-stricken protagonist is appalling. Yet the juxtaposition is also mordantly satiric in its cruel, Swiftian incongruity. Milder, but likewise drawing on satire, is First Lady (Pat Nixon), which shows the golden-gowned and golden-haired presidential trophy wife posed formally at the mantelpiece of a golden-papered and golden-upholstered salon in the White House. Above the mantelpiece appears a gilded picture frame that would have contained an oval oil painting, probably a portrait. Rosler has replaced whatever was actually there with a black-and-white detail from the brutal finale of Bonnie and Clyde (1967), in which the title character played by Faye Dunaway is machine-gunned to death in a police ambush.

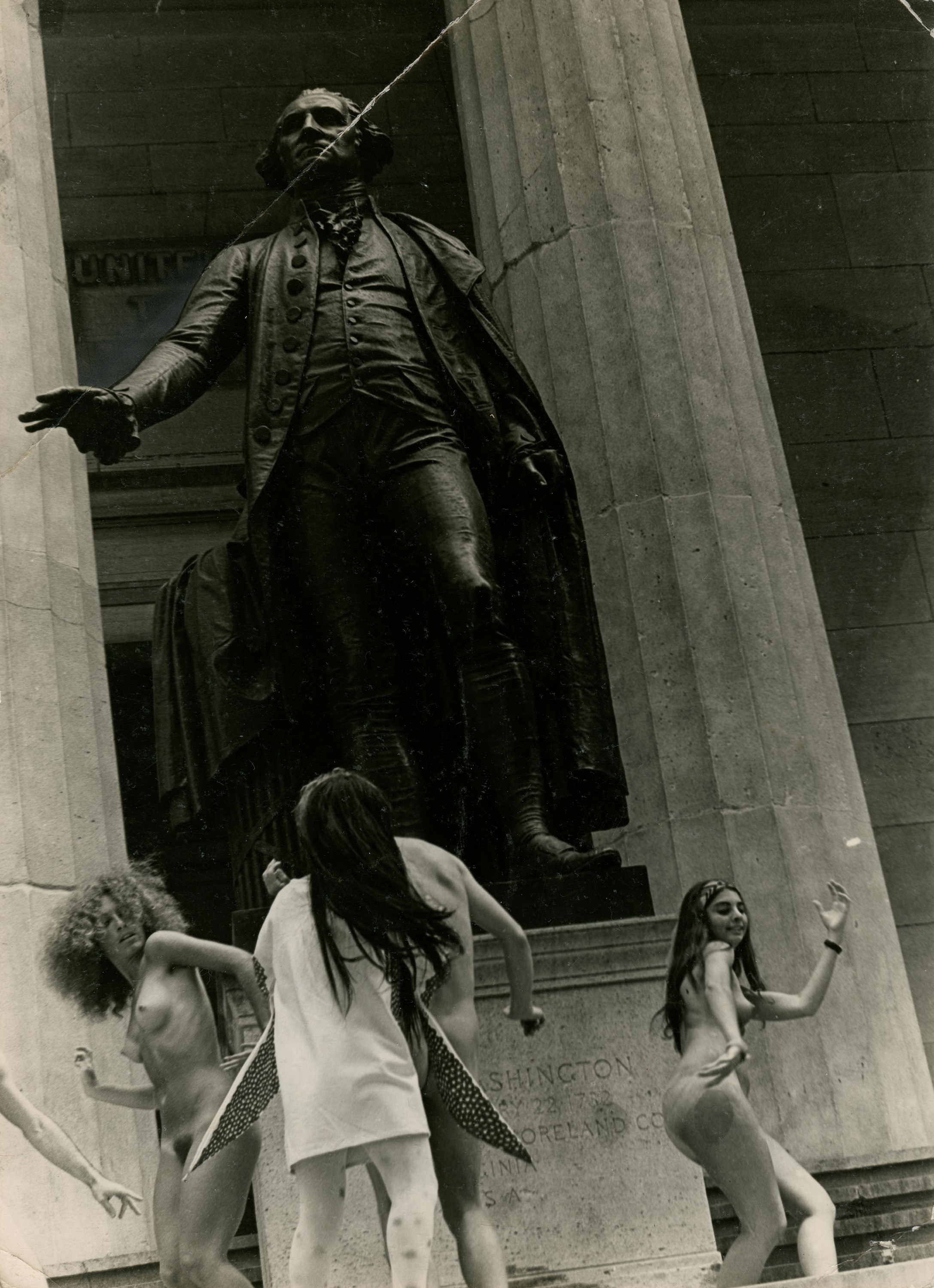

Fig. 3, Yayoi Kusama, Anatomic Explosion on Wall Street, 1968. Performance photograph; exhibition copy, 14 x 11 in. Courtesy of Yayoi Kusama Inc.

A sort of Merry Prankersterish, Abby Hoffmanish, Yippie humor informs two 1968 Happenings by Yayoi Kusama, known collectively as Anatomic Explosion on Wall Street. Kusama, a Japanese-born painter turned performance artist, enlisted four dancers—two men and two women—to strip naked on Wall Street and frolic with Dionysian gyrations at the base of the iconic statue of George Washington on the steps of Federal Hall. In a photograph documenting the encounter (fig. 3), the hero of the American Revolution, who was once an inspiration to revolutionaries around the world, including Ho Chi Minh, appears to be pushing away the unruliness below. He looks disgusted, repulsed by the pesky, dirty, naked bacchanalians undulating at his feet. The punning title, collapsing “An Atomic” into “Anatomic,” alludes to the destabilization of the establishment by the so-called youthquake of the antiwar movement. In the mise-en-scène of the photograph, with its skewed angles and two-tiered layout, the joyous young dancers, unfettered by clothing, undermine the stern and stodgy general. Samson-like, they seem ready to topple him and the Temple of Mammon over which he presides.

To be sure, dancing naked in the streets did not truly threaten the military-industrial complex symbolized here by the conjunction of Washington and Wall Street. But nor were politically motivated Happenings such as these simply frivolous fantasies of anti-government power by those who in reality had none. Instead, they might be thought of as morale-boosters and community-builders for the antiwar campaign, much the same as “We Shall Overcome” and other so-called Freedom Songs instilled strength and courage in Civil Rights activists during their darkest hours. Anatomic Explosion on Wall Street figuratively put flesh on the familiar slogan “Make Love, Not War” and, in doing so, provided the antiwar base with a utopian glimpse of a repression-free future. Its goal was to create for its partisans a sort of psychic, rather than physical, nuclear fission.

Philip Guston, the distinguished Abstract Expressionist painter, jeopardized his critical reputation when he renounced cool, detached, formalist abstraction for hot, cartoonish, intentionally vulgar antiwar satires that included a series of caustic caricatures of Richard Nixon. He just could not see any other way of being both an artist and an activist—an artist who patriotically served the republic by standing up against the War Machine that perverted its principles. He asked himself, with self-deprecating humor, “What kind of man am I, sitting at home reading magazines [about the war], going into a frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”2

One last example of the multiple senses of humor so liberally displayed in Artists Respond is a reinstallation of Hans Haacke’s News (1969), originally mounted at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1970 (fig. 4). In the present exhibition, resting on a table is an old-fashioned dot matrix printer that noisily and incessantly prints out rolls of real-time feeds from an actual wire service, daily news in 2019. Teletype paper blackened with ink spews out of the printer onto the gallery floor in crazy coils and random loops. These Mobius Strips accumulate into a mountain—or cloud—of information run amok. Placed centrally in the last suite of the exhibition, the installation is impossible to tune out, regardless of what other work you might be trying to contemplate. Its visual clutter and aural clatter are unavoidable, like news itself in the modern world. Insistently demanding our attention, it seems to exert a will of its own.

Fig. 4. Hans Haacke, News, 1969, reconstructed 2019. Newsfeed, printer, and paper, dimensions variable. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Purchase through gifts of Helen Crocker Russell, the Crocker Family, and anonymous donors, by exchange, and the Accessions Committee Fund

In Goethe’s 1797 poem “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” which was set to orchestral music in the late nineteenth century and given the Disney treatment in Fantasia (1940), the assistant to an absent magician tries to save time in his chores by commanding a broom to fetch pails of water for him. The broom speeds up the activity by subdividing into a proliferating army of smaller brooms, which also fetch water and empty it on the floor, flooding the chamber because the apprentice has no idea how to stop the monster he has created. Haacke’s News is a realization of Goethe’s cautionary tale about the perils of mechanization gone rogue. It updates Fantasia for a wartime society in which knowledge may be a form of power, but too much knowledge incurs distraction, and therefore powerlessness.

One of the most satisfying elements of Artists Respond is its ethnic, racial, and gender inclusivity. It features art by numerous well-known and lesser-known African American, Asian, and Latinx artists, many of whom are female. Among these female artists, in addition to Rosler and Kusama, are Judith Bernstein, Rosemarie Castoro, Judy Chicago, Corita Kent, Yoko Ono, Liliana Porter, Yvonne Rainer, Faith Ringgold, Carolee Schneeman, Nancy Spero, May Stevens, and Carol Summers.

In manifesting such a capacious diversity of artistic responses to the Vietnam War, the exhibition makes an important point for art-historical revisionism. A handful of canonical modernists, Minimalists, and postmodernists are represented in the exhibition: Carl Andre, Dan Flavin, Guston, Donald Judd, Newman, Ad Reinhardt, Robert Smithson, and Mark di Suvero, among others. But the majority of artists included were far removed from canonical status in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The war, as much as anything, perforated the canon, opening it up for types of art and artists that heretofore would not have been given serious consideration by the leading authorities of the art world.

In this regard, some of the art in the exhibition attacked separate, yet overlapping, establishments. One of these was the political realm of Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, Wall Street warmongers, and the arms industry. The other was the aesthetic realm of Greenbergian art formalists and politics-shunning abstractionists who at the time dominated art journals, art magazines, art schools, and art museums. These two establishments coincided most visibly in the case of four-term Republican governor Rockefeller, a Nixon supporter who also served as a trustee of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The governor’s oil-rich mother, with a couple of her wealthy friends, had founded the museum in 1929.

Four decades after that founding, the Guerilla Art Action Group staged an unauthorized Happening in the lobby of MoMA that became known as Bloodbath (1969). Four performance artists strapped to bags of fresh beef blood flung into the air hundreds of copies of a statement headed “A Call for the Immediate Resignation of All the Rockefellers from the Board of Trustees of the Museum of Modern Art.” They then pretended to attack one another, unleashing the pseudo bloodbath while crying murder and rape. The whole action lasted no more than five minutes. The statement they scattered indicted the Rockefellers for, among other things, the “use of art as a disguise, a cover for their brutal involvement in all spheres of the war machine.” Given the recent and ongoing protests against “dirty” trustees and donors of major art museums, Bloodbath seems painfully prescient.

Artists Respond is a remarkably polyvocal exhibition, to be applauded for its diversity, although a visitor might wonder how politically and aesthetically conservative artists of those years also responded to the war. A more accurate title for the show might be Artists Protest, since principled resistance to the war is the single, unifying mode of response put forward. Similarly, one would like to know how Vietnamese artists portrayed the war from their perspective during those same years, but this was clearly not within the purview of the exhibition and should not be seen as an omission. Indeed, SAAM has thoughtfully paired Artists Respond with a much smaller exhibition of work by the contemporary Vietnamese American mixed-media artist Tiffany Chung that retrospectively examines the war and its legacy from the perspective of its Vietnamese survivors.

In her illuminating introduction to the catalogue, Melissa Ho explains why the exhibition provides no examples of pro-war art: “That no art in the exhibition expresses full-throated support for the U.S. war effort both reflects the widespread unpopularity of the conflict in the late 1960s and confirms the inclination of modern artists to identify with progressive or utopian projects.”3 This is undoubtedly true, but still, the national museums of the various military services maintain respectable art collections that are open to the public for viewing and study. Future historians of the Vietnam era might do well to explore the art that a vast number of Americans found conducive to their understanding of the geopolitical conflict, even if—especially if—it led them toward false and dangerous conclusions.

But that sort of comparative study of opposing American political and aesthetic cultures is not the purpose of this exhibition. The goal of Artists Respond is to demonstrate the unrelenting courage of activist artists to fight for the hearts and minds of their fellow citizens during a period of extreme ideological fracture, and in this it has amply succeeded.

Cite this article: David M. Lubin, review of Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965–1975, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 5, no. 1 (Spring 2019), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1712.

PDF: Lubin, review of Artists Respond

Notes

- Robert Cozzolino, catalogue entry for Barnett Newman in Melissa Ho, ed., Artists Respond: American Art and the Vietnam War, 1965–1975 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian American Art Museum, in association with Princeton University Press, 2019), 125–27. ↵

- Philip Guston as quoted in Melissa Ho, “One Thing: Vietnam,” in Ho, ed., Artists Respond, 11. ↵

- Ho, “One Thing,” 4. ↵

About the Author(s): David M. Lubin is the Charlotte C. Weber Professor of Art at Wake Forest University